Sugar and Lumber: The Historical Roots of Floods in Negros

When it comes to marital vows in the Visayas, there is one that unfortunately stands the test of time despite the many challenges hurled at it: the bond between capital and calamity in Negros. Wherever one is, the other is also present or sure to arrive. This malicious matrimony was inaugurated on the island in the 1850s, back when British commercial interests conspired with local capitalist ambitions, ushered in by the imminent collapse of the textile industry in Panay.1 Despite their notorious beginnings, the couple are never shy to celebrate their enduring covenant, as even today they lavish the island with routine disasters to commemorate their accursed union. Thus, when capital figuratively flooded into the island, calamity literally followed: because before floods became the hallmark of DPWH projects, Negros was swimming in waters that were entirely unprecedented and, lamentably, preventable.

The principal sponsors of this marriage were, of course, the hacenderos. As is typical of tragedies in Negros, they are, unsurprisingly, deeply involved: either directly or indirectly, and almost always to a significant degree. Their persistent imprint is strikingly evident in the many flooding events that regularly punctuate the island's history.

The colonial archives contain state and clerical reports from the 17th and 18th centuries documenting intermittent floods in Negros. None, however, were of great tragic rank. The island's forests still excelled at their venerable task of absorbing rainfall and regulating river flows. Annual floods were expected and quite normal, depositing silt and rich amounts of nutrients along riverbanks. The island's robust ecological condition then was more than capable of handling the more turbulent episodes, thus limiting casualties. Arguably, the first instance of a destructive inundación (flood) on the island occurred in April 1872, a subtle foreshadowing of disasters to come.2

Enter: the hacenderos. For these nascent capitalists to prosper, they converted large tracts of land for sugar monocropping, land initially teeming in biodiversity. Among these emerging figures was Juan Araneta, one of the leaders of the Cinco de Noviembre revolt of 1898, and a foremost example of this grand land conversion. With his prominent stature and almost mythical eminence, Araneta was able to incorporate 5,000 hectares of land into his hacienda.3 One cannot help but look aghast at the gravity of environmental destruction that must have taken place to convert such magnitude of land for the production of a single commodity. Worse still, the vastness of Araneta's land was neither unique nor surprising. It represented the norm—a grim indicator of the extent of land appropriation that had occurred and was occurring on the island. By the turn of the 20th century, Ilonggo hacenderos were already spread across the island like a particularly virulent fungus. The Gastons, Lacsons, Lopezes, Benedictos, Locsins, Montillas, Luzuriagas, de la Ramas, Yulos, Aranetas, and others had been producing sugar for quite some time and were reaping high profits.4 While most of them trace their roots back to Panay, there were also migrants from elsewhere that joined this motley medley. After his visit to the island, the German explorer Fedor Jagor notes that there were “as many as twenty Europeans established on the island of Negrós as sugar planters” by the 1860s.5 The entirety of Negros was being recast as one contiguous sugar monoculture, its once vibrant landscape turned into a homogenised hell.

The havoc wrought by the hacenderos' relentless pursuit of profit is not theirs to bear; instead, the ordinary residents of Negros, who had no hand in the creating such conditions, are forced to endure the heightened consequences of the island's fractured ecology. The native flora, ancient and essential to the island's natural stability, was violently wrenched from the earth to make way for endless rows of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum). The resultant vista is dominated by a mere grass, of little use in mitigating the effects of voluminous rainfall and bellowing winds, making floods and damage from typhoons almost inevitable. Yet, while many are swept by these torrents, especially the poor plantation workers, the hacenderos sit comfortably in their palatial homes or in their expensive houses away from the island, safe from the perils they have helped conduct. Indeed, as history shows, the island of Negros and its inhabitants are mere collateral damage to the capitalist pursuits of the hacenderos.

Their rise to power exhibits this tendency well.

While modern depictions often portray the Negros hacenderos as courageous heroes who drove the Spaniards out of the island after a successful revolt in 1898, they were, in reality, the prime beneficiaries of colonial protection and accommodation. Some, displaying outright endorsement of colonial rule, even served as auxiliaries to the Spanish state. Aniceto Lacson, for instance, leased portions of his land to the government for a substantial sum: it was to be used by the Guardia Civil as a sentry point to watch for renegade plantation workers.6 Their sympathies only changed when the alluring prospect of doing permanent business with the Americans loomed over the horizon, and turning their backs on their erstwhile Spanish masters was the easy and commercially profitable decision.

Figure 1: Newsclip from the Manila Standard.

In siding with the new colonisers, the hacenderos did not just declare their capitalist intentions, but also inadvertently championed the primacy of class interests over cultural identity. When they stood up against the Spaniards just to immediately kneel before the Americans, they betrayed the very people who looked up to them as liberators and colleagues. Indeed, the evidence of this capitulation emphatically illustrates this penchant for opportunism. According to the 1900 Report of the Philippine Commission, a few days after 5 November 1898, “Mr. Lacson, the president of Negros; Mr. Luzuriaga, the president of the congress, and two younger men” prostrated themselves before the Americans and declared “that they had come to offer unconditional adherence to the American Government; that they wished for the protection of the American Government, and for the assistance of the American Government in maintaining peace and order in the island.”7 This was hardly surprising. Capital recognises no flags, only profit margins.

The Americans, having secured hacendero submission, immediately explored the island to determine its economic potential and catalogue its profitable resources. It was not long before they took notice of the towering trees—like the lauan, apitong, maluwin, narra, almon, and mankono to name a few—which stood in abundance especially in the north.8 “A considerable proportion of the northern half of the Island of Negros is covered with forests,” declares the 1913 report of the Bureau of Forestry, “which are estimated to contain eight billion feet of timber, more or less, and which constitute what is probably the finest stretch of unbroken woodlands in the Philippines to-day [sic].”9

For the Americans, there was nothing to gain in leaving this “finest stretch” untouched. Without much in motivation aside from sheer profiteering, the Americans quickly set to work. They came up with a plan that was both simple and severe: these ancient trees were to be cut, processed, and sold to the global market.

Thus, in 1903, the colonial administration granted the Iloilo Electric Company (IEC) a license to cut over 100,000 cubic feet of timber from the northern forests of Negros. The following year, the Insular Lumber Company (ILCO) was established in Fabrica, Sagay, assuming control of IEC's logging operations and securing a 20-year concession to further exploit the forests for timber.10 Subsequently, the Negros-Philippine Lumber Company built its mill on the coasts of Cadiz. Though smaller than ILCO, it nevertheless was able to produce 20,000 board feet of lumber daily.11 The now-ruling hacenderos had officially sanctioned the American destruction of Negros' forests.

With capital now firmly in place, calamity was on its way. In September 1909, The Cablenews-American reported how “the Tamogon river at Bais had overflowed, inundating the provincial wagon road to the depth of one meter.” Five houses were swept away and five people drowned.12 The precise cause of this flood remains uncertain. Nevertheless, as the years went by, it became increasingly evident that the thread connecting lumber, sugar, and floods was coiling around the island's neck, getting tighter and tighter.

Figure 2: An American poses heroically on a cut lauan. Promotional material from ILCO.

For the residents of Negros, rivers were indispensable, serving as a primary source of drinking water, a washing area, a convenient waterway, and as a ready basin of fresh food. This vital relationship, however, dramatically shifted as rivers turned into a destructive force, bringing widespread death and devastation.

In 1912, another report from The Cablenews-American noted that the “greater part” of Negros Occidental “is inundated”. The hacenderos were greatly affected, not because some of them died, but because they “have lost practically all of their live stock [sic] and work animals.” Unlike the hacenderos who can only lament the loss of their business assets, the devastation to the ordinary people was truly catastrophic, with countless families perishing and entire neighbourhoods decimated. At the time of reporting, the total casualties in Escalante and Talisay were yet to be fully counted, but in Bago there were already 80 confirmed dead and 14 in Hinigaran. What became clear was that the rivers were now taking a more sinister route: from being the primary provider of water, enabling life, it was now an erratic whip, lashing out at the inhabitants with liquid flushes of cataclysm. The report added that “the Imbang, Binalbagan, Matabang, Bago and rivers [sic]” rose to heights exceeding “their banks and running in raging torrents over wide sections of the country.” Moreover, the Cabancalan river in Talisay plunged its surroundings “to a depth of three feet, killing many people and practically every work animal in the district.”13

The role of deforestation in exacerbating floods is well documented and supported by scientific research. According to meteorologist and hydrologist Colin Clark, rich-canopied forests provide a dual function: first, about one-third of rainfall “is intercepted and evaporated by the tree canopy.” Second, as above, so below, forests greatly contribute to keeping river levels from overflowing by creating deep channels in the soil for water absorption. Clark explains that “forest soils are about seven times as permeable to rainfall as are the soils of pasture-land.” When forests are cleared, “within a few years the channel would be unable to adjust to the rapid increase in flood discharge and the water-level would be considerably higher than before.”14 Stripped of its ancient forests, Negros was now utterly defenseless, more vulnerable than at any time in its history. However, the logging companies and the hacenderos took no drastic step to ensure the survival and restoration of the forests. Instead, they utilised the now erratic rivers to their advantage.

It was a toast yet again to the conjugal crux of capital and calamity.

To transport massive logs from mountain elevations down to shipping ports, the lumber companies employed rivers as makeshift conveyor belts. This was a necessary adaptation to the rugged terrain of tropical forests. In their early years, the loggers in Negros were still trying to familiarise themselves with this scheme, as there were times when rivers overflowed and destroyed their machines or sent their precious logs downstream out to sea.15 Inexperience cost them money, like in 1917 when “[a] violent flood for a time interrupted lumbering at Fabrica and Cadiz, but the chief obstacle met with by all licencees was the lack of shipping.”16 The more they cut their way through the forests, the more they became familiar with the island's climatic tempers. To master these cycles was therefore of utmost importance, as it ensured the smooth going of their operations leading to, of course, profits while minimising losses.

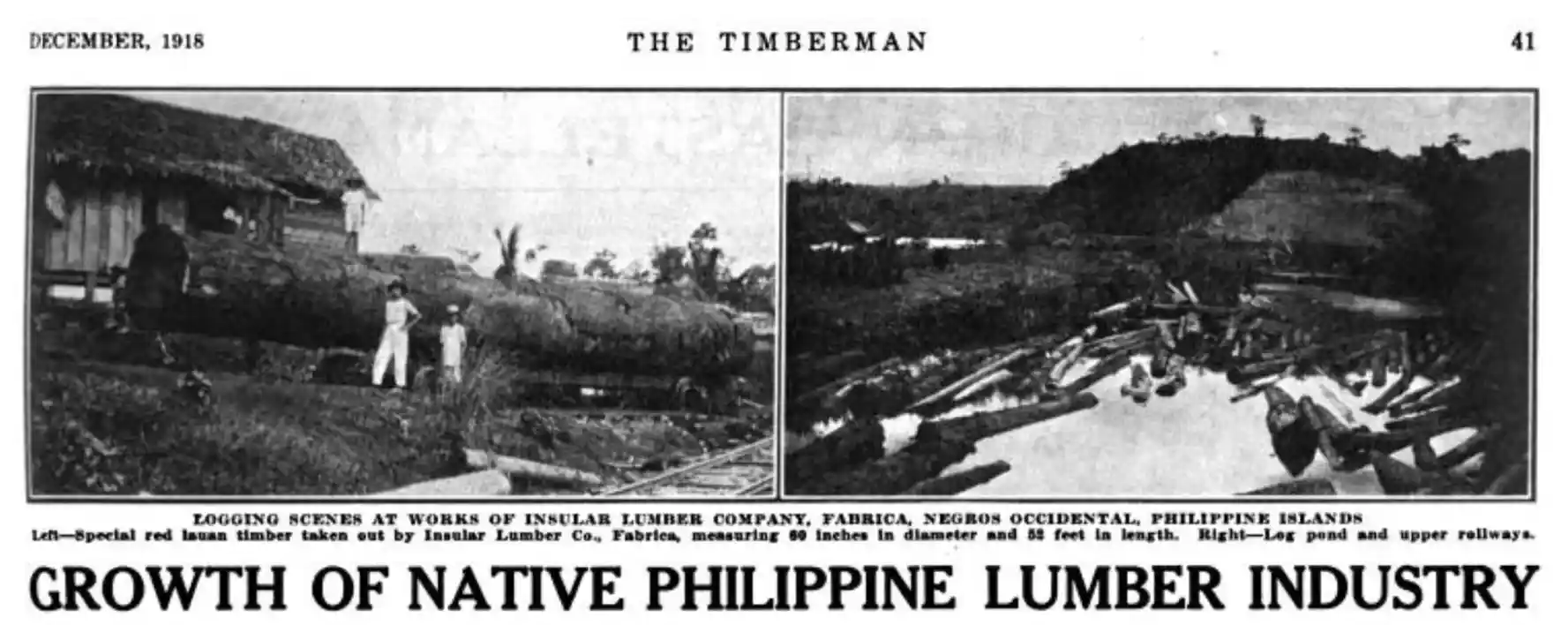

Figure 3: Clip from The Timberman on the beginnings of the lumber industry in Negros.

One innovation these logging companies enacted was to construct artificial lakes, ponds created by damming and diverting streams, to store logs awaiting transport. When sufficient lumber had accumulated, they would release the dammed water in controlled floods, sending large amounts of timber careening downstream in a manufactured deluge.

Manipulating rivers wasn't a technique solely employed by the logging firms. The hacenderos also diverted rivers to their plantations, creating new channels from established streams to irrigate their fields, as sugarcane is a water-intensive crop.17 Active rivers, therefore, became not merely instrumental but essential to the business model of hacenderos and the logging companies. The latter raised water levels high enough for more lumber to be carried downstream while the former ensured that the fields were well hydrated. However, both also dumped their industrial discharges into the streams, thereby polluting them and inadvertently harming local communities who depended on riverwater to live.

Over time, the denuded mountains of Negros, devoid of its crowning canopies, could no longer absorb rainfall. The riverbeds, scoured by the repeated battering of logs, lost their natural capacity to regulate water flow. This destructive combination culminated most dramatically in 1984, when Typhoon Nitang (internationally known as Ike) ravaged through the Visayas.

Not content with the profits raked in with sugar, the Gatuslaos of Himamaylan established the Negros Industrial Development Lumber Company (NIDCO) in the 1930s, though it was locally known as Batman Logging due to its owner's eccentric personality. Located in the hinterlands of Carabalan, NIDCO was the biggest of its kind in this section of the island, reaching a daily production capacity of 20,000 board feet of lumber in 1944.18 This lumbering activity coupled with the Gatuslao's sugarcane production further worsened the ecological and hydrological conditions of central Negros, resulting in the aforementioned tragedy of 1984. This catastrophe was captured in vivid detail in Alan Berlow's Dead Season:

“The Gatuslaos had a legal right to cut timber, and their wealth and political power allowed them to go about their business with impunity. Nothing demonstrated this more baldly than Typhoon Nitang, which slammed into Negros in September 1984, dumping a torrent of rain onto the mountains. The Visayan Daily Star reported that more than 7,000 homes were destroyed and more than 100 people killed as a flash flood thundered from the mountains, carrying gigantic logs through populated areas. The Bureau of Forest Development blamed the disaster on Batman Logging but took no action against it.”19

While many suffered from the floods and deforestation, the hacenderos reaped substantial benefits. The clearing of forestlands provided them with available area to expand their holdings. In fact, some hacenderos even invited lumber companies to clear forests for agricultural expansion. This was part of ILCO's genesis and convenient placement in the middle of the forests of northern Negros. The upstart Gil Lopez was able to acquire 1,500 hectares of land from the government, which he subsequently cleared with the help of ILCO. According to his grandniece Maria Lina Santiago, Lopez “invited American businessmen to infuse the capital needed for the development of wood products. As a result, Fabrica Insular Lumber Company was established.” The aged trees that made up the “dense and impenetrable” forests were no match for this onslaught. So wholesale was the destruction that even the native wildlife, like “gigantic pythons were not spared.” Moreover, the speed and scale by which Lopez and ILCO destroyed the forest was so sweeping that Santiago describes ILCO, almost with a touch of pride, as “the biggest hardwood company in the world then.”20

Figure 4: Lumbering activity in Northern Negros in 1910.

While there is a hint of restraint in Santiago's fêting of her kin with such dubious prestige, the many grand hacendero mansions across the island boldly display the polished carcasses of the fallen trees. Once processed, local timber was then shipped to Manila showrooms before being sold onto the global market. A fraction of these woods, however, found their way back, completing a morose homecoming from native giants to foreign commodities, only to return to the island as a morbid trophy of environmental conquest. Often, their final destination was the very abodes of the people who signed their lucrative obituaries. “In Negros”, writes the Director of Forestry in 1915, “the demand for timber was great, mainly for the construction of hacienda buildings.”21 These grand structures stood as monuments to hacendero wealth, built from the very resources whose removal endangered the communities outside its boundaries. The ancient forests that had once been a communal source of sustenance and protection were transformed into expensive commodities and decorative pieces priced far beyond the reach of ordinary workers, reinforcing the paradoxical state of poverty where one could be surrounded by such wealth but have no claim to it.

Given their immense economic and political influence, the hacenderos were in a crucial position to address the burgeoning ecological and social crises. They had both the means and influence to enact stronger environmental policies, mobilise effective reforestation efforts, or devise flood control projects that incorporated natural systems. Instead, they did none of these. Their political engagements were fuelled by the simple desire to use the mechanisms of the state to further their own commercial interests. Politics was simply a tool to secure more capital. This priority is starkly illustrated by their manipulation of the state's financial institutions. Historian Yoshiko Nagano notes that the Agricultural Bank had already been co-opted to serve large landlords, and when even that proved insufficient, they used their power to get more. “In 1913,” says Nagano, “during the Third Philippine Legislature, Assemblyman Montilla of Negros Occidental introduced a bill to appropriate one million pesos in funds” to increase the Agricultural Bank's lending capacity.22 While the island's denuded mountains bled soil into the rivers and the floods grew more severe over time, as testified by the tragic floods the year prior, the hacenderos' primary legislative concern was not to exhaust all political means to prevent such from happening again, but securing another million pesos for their plantations.

The political priority for profit security over preservation provides the final, damning evidence of where hacendero concerns lay. For them, floods were never tragedies to be mitigated; they were externalised costs of doing business, mere byproducts of their continuous accumulation. This is why, even today, when the rains come, the island does not just suffer a weather event: it discloses a historical debt. The torrents are a physical mnemonic, a persistent reminder that every ounce of floodwater carries the weight of a century of deforestation, monocropping, and colonial-era concessions. Streets awash in silt are graphic reminders of the massacre in the mountains that eradicated a once-robust ecology, violently slaughtered for sugarcane plantations and commercial gain.

The fatal bethrothal between capital and calamity continues to enshrine the cyclical catastrophes in the island. The historical burden of environmental and economic exploitation is forever embedded in the rising water lines, and the island remains submerged, not just in rainwater, but in the corrosive economics built in the past. Until the island's economy is finally divorced from the dictates of capital, the waters will continue to rise, and Negros will remain hostage to the disastrous vows taken over 170 years ago.

Footnotes:

Ulbe Bosma, The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years (Massachussets: The Belknap Press, 2023), 135.

Emmanuel Luis Romanillos, “Events in Bacolod, Negros Occidental, in the Parish Chronicle (1871-1909) of Fr. Mauricio Ferrero, OAR and Other Essays” (Bacolod City, 2016), 2.

Filomeno Aguilar, “Masonic Myths and Revolutionary Feats in Negros Occidental”, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 28, no. 2 (1997): 295–97; , Alonzo Stewart, “Agricultural Conditions in the Philippine Islands”, Government Report (Department of Agriculture, 1908), 23.

Alfred McCoy, “A Queen City Dies: .The Rise and Decline of Iloilo City”, in Philippine Social History: Global Trade and Local Transformations, ed. Alfred McCoy and Ed de Jesus, vol. 7, Southeast Asia Publications Series (Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1982), 315–16, 321; , John Larkin, Sugar and the Origins of Modern Philippine Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 65.

Fedor Jagor, Travels in the Philippines (London: Chapman and Hall, 1875), 306.

Dirrecion General de Administracion Civil, Expediente sobre distribucion y cambio de puestos de Guardia Civil en el Sitio de Pantayanan del pueblo de Minuluan (1892), Philippine National Archives.

“Report of the Philippine Commission to the President”, Government Report, vol. 2 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900), 335–56.

Harry Day Everett and Harry Nichols Whitford, “A Preliminary Working Plan for the Public Forest Tract of the Insular Lumber Company, Negros Occidental, P.I.”, Government Report (Manila: Bureau of Forestry; Bureau of Printing, 1906), 16.

George Ahern, “Annual Report of the Director of Forestry of the Philippine Islands for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1913”, Government Report (Manila: Bureau of Forestry; Bureau of Printing, 1913), 13–14.

Everett and Whitford, “A Preliminary Working Plan for the Public Forest Tract of the Insular Lumber Company, Negros Occidental, P.I.”, 32–33.

Hebert Stout, “The Northern Negros Forest”, Forestry Quarterly 10, no. 4 (1912): 620.

“Five People Drowned”, The Cablenews-American, no. 487 (1909): 1.

“Wind and Flood Damage Negros”, The Cablenews-American, no. 329 (1912): 1.

Colin Clark, “Deforestation and Floods”, Environmental Conservation 14, no. 1 (1987): 67–68.

“Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Forestry of the Philippine Islands for the Period from September 1, 1903 to August 31, 1904”, Government Report (Manila: Bureau of Forestry; Bureau of Public Printing, 1905), 14–15.

“Annual Report of the Director of Forestry of the Philippine Islands for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 1917”, Government Report (Manila: Bureau of Forestry; Bureau of Printing, 1918), 20.

Willem Wolters, “Sugar Production in Java and in the Philippines during the Nineteenth Century”, Philippine Studies 40, no. 4 (1992): 429–30.

Far Eastern Unit, “Philippine Islands: Natural Resources”, Civil Affairs Handbook (Washington: Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce; Army Service Forces, 1944), 25.

Alan Berlow, Dead Season, 1st ed. (New York City, New York: Pantheon Books, 1996), 146.

Maria Lina Santiago, Araneta: An Affair with God and Country (Quezon City: Sahara Heritage Foundation, 2007), 160; , Louis Borja, “The Philippine Lumber Industry”, Economic Geography 5, no. 2 (1929): 201.

W.F. Sherfesee, “Annual Report of the Director of Forestry of the Philippine Islands for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 1915”, Government Report (Manila: Bureau of Forestry; Bureau of Printing, 1915), 33.

Yoshiki Nagano, “The Agricultural Bank of the Philippine Government, 1908–1916”, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 28, no. 2 (1997): 316–20.